DIGGING INTO MY CRATES: Lee Morgan's The Sidewinder

The perennial Blue Note chestnut album, title track and all, just got added to the same Class of 2024 National Recording Registry as Green Day's Dookie and Biggie Smalls' first album. I approve.

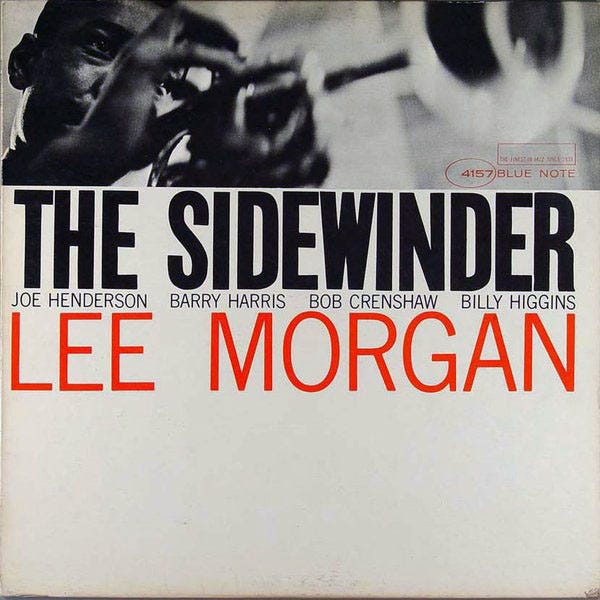

LEE MORGAN

The Sidewinder

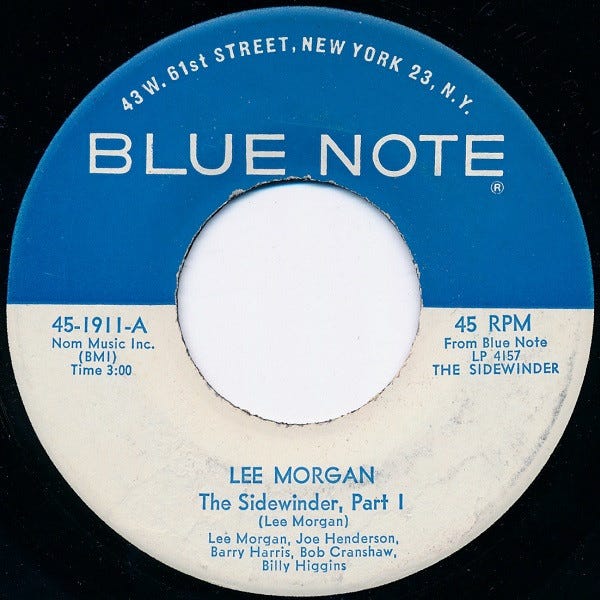

(Blue Note/Capitol/UMG) (LP, CD, digital)

MUSICAL PERSONNEL: Lee Morgan (trumpet), Joe Henderson (tenor sax), Barry Harris (piano), Bob Crenshaw (bass), Billy Higgins (drums)

PRODUCER: Alfred Lion

ENGINEER: Rudy Van Gelder

RECORDED AT: Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, December 21, 1963

Original release date: July 1964, on mono and stereo LP and 7.5 IPS reel-to-reel

The yearly announcement of the newest candidates to be preserved for the National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress seems to be one of the more anticipated events amongst music lovers – and appears to be that one event where, unlike announcements of Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame inductees and Grammy Awards nominations, the poison pens get kept in their desk drawers and the keyboard warriors take their hands off the keyboards for something other than fapping to PornHub uploads. And one of the selected titles this year made it almost mandatory to hold off on doing the next installment of Tranespotting this week in favor of doing something else jazz-related right now.

One of two jazz entries in the National Recording Registry Class of 2024 (the other is the Benny Goodman/Charlie Christian song “Rose Room,” instantly recognizable to anyone who owns the DVD box set to Ken Burns Jazz) is also the latest platter from Blue Note Records to get it’s due at the Library of Congress: Lee Morgan’s breakthrough album, The Sidewinder. (Now, granted, some jazz fans might be bristling at the fact that the year before, an album by noted jazz luddite Wynton Marsalis [who was lucky to end up number two on Miles Davis’ shitlist behind musical wallpaper merchant Kenny G] was shortlisted by the Library of Congress – but not as much as some basement-dweller might be when an artist whose music doesn’t involve Marshall amps and Aqua Net makes the Rock Hall.)

Morgan’s album is in good company at the LofC just on a jazz level alone – two John Coltrane albums, Giant Steps and A Love Supreme, are there, as is Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue (which, of course, also features Coltrane prominently), Ornette Coleman’s The Shape Of Jazz To Come, Thelonious Monk’s Brilliant Corners, Dexter Gordon’s GO, Vince Guaraldi’s A Charlie Brown Christmas (don’t laugh – it’s the second biggest selling jazz album behind Kind of Blue), Sonny Rollins’ Saxophone Colossus, and Pat Metheny’s Bright Size Life, to name quite a few selected as examples based on their being favorites of mine. It’s one of Blue Note’s many classic albums. It has rarely, if ever, gone out of print – and has been one of many Blue Note titles frequently earmarked for audiophile quality reissues by the likes of Music Matters and Analogue Productions.

Had he not been murdered in cold blood in public in 1972, it would be interesting to find out Morgan’s reaction to this album being chosen for preservation. That’s because Morgan felt that the song that ended up being the album's title track was more of an album track – dare anyone say, filler material, god forbid? – than a highlight of the late December session at Rudy Van Gelder’s second studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. It was mostly a typical Blue Note session with label co-founder Alfred Lion in the producer’s chair and Rudy Van Gelder operating the mixing desk and the tape machine.

In fact, to Morgan himself, it was a bit of a comeback with regards to his return to Blue Note after a couple of years away from the scene as both a solo artist and a member of Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers – and that time away, spent in his hometown of Philadelphia, was because he’d been dealing with a heroin addiction that he would never be fully able to shake. (And Blakey is said to be part of Morgan’s heroin problem, as Blakey reportedly used to pay his sidemen in smack to control them.) His previous album, Take Twelve, was done for Riverside via their side label Jazzland, and the one before that, Expoobidient, came out on VeeJay.

The title track is instantly recognizable, a 24-bar blues variant with Morgan and saxophonist Joe Henderson playing the two-part harmonized melody. In contrast, the rhythm section of pianist Barry Harris, bassist Bob Cranshaw, and drummer Billy Higgins play what would become known as a “soul-jazz” groove behind them. The song is also so immortal and timeless that it’s been a mandatory inclusion in any Blue Note best-of CD anthology that has ever existed – and another page in the book of jazz standards, having been covered entirely a few times. (Check out Akiko Tsuruga’s organ-jazz take of the song on her 2009 album Oriental Express for the closest the world will ever come to imagining how Jimmy Smith or Akiko-chan’s mentor, Dr. Lonnie Smith, would have done it.) It ended up in a Chrysler commercial in 1964 – without the permission of either Morgan or Blue Note, who sued the automotive giant and got an amicable settlement (by 1965 standards) out of court. All five of the tracks on the original album (an alternate take of “Totem Pole” is on the CD release) were Morgan originals, suggesting a renewed focus (although, to be accurate, Morgan had written every track on Take Twelve as well) on his music.

The title track was pretty near a stylistic anomaly compared to the rest of the album, which remains closer to the usual bebop and post-bebop template, with “Totem Pole” the track that alternates between both the bop and soul-jazz forms. But somehow, it clicked. Blue Note, then still an independent label and a couple of years away from being sold to Liberty Records, had only pressed 4,000 copies initially – but they sold out within a week.

The album was a blessing and a curse for all involved. Its surprise success bolstered Blue Note’s viability when they desperately needed it (hence one of the reasons they only did a first pressing of four thousand copies). Morgan, who had subsequently recorded two more albums, Search for the New Land and Tom Cat in 1964, found himself seeing both albums get shelved when Alfred Lion prodded him to write more material in the style of The Sidewinder’s title track – hence the actual follow-up to Morgan’s biggest hit album, The Rumproller. (Search for the New Land would get released eventually in 1966, but Tom Cat remained shelved until 1980, eight years after Morgan’s death by homicide.) Most of Morgan’s subsequent albums would find him forced to keep copying the Sidewinder formula. And Morgan’s substance abuse issues would manifest themselves again, with the proceeds from the Chrysler settlement and Morgan’s Sidewinder royalties going into Morgan’s arms – and no doubt, the pressure of seeing his more serious sessions being shelved indefinitely in favor of more Sidewinder sequels.

Within a decade, Alfred Lion would be gone from the label he co-founded, Morgan would be gone, period, and Blue Note’s other co-founder Francis Lloyd would be both – leaving the label in 1967 and dying the year before Morgan’s death. Lion sold Blue Note and Lloyd to Liberty Records in 1965 – partly because Blue Note needed to be able to keep doing new pressings of their hit albums; that label itself was bought by United Artists in 1971; United Artists Records would be absorbed by Capitol/EMI in 1979, and EMI would phase out Blue Note as an active label until 1985. Since its revival, Blue Note became Capitol/EMI’s flagship jazz label, absorbing the responsibility for preserving all of the other jazz recordings under the Capitol banner and later giving rise to the Blue Note Label Group in 2005, all the while ensuring the immortality of Blue Note’s substantial (and growing) back catalog of recordings – including The Sidewinder, which has followed into the next level of immortality over at the Library of Congress.