DIGGING THROUGH MY CRATES: How Your Humble Author Started Delving Into Jazz, Parts 1 & 2.

I always tell anyone asking me hwo to get into jazz to buy "Kind Of Blue" and "A Love Supreme" first. Admittedly, this is a case of do what I say, not what I did - but I still got into jazz anyway.

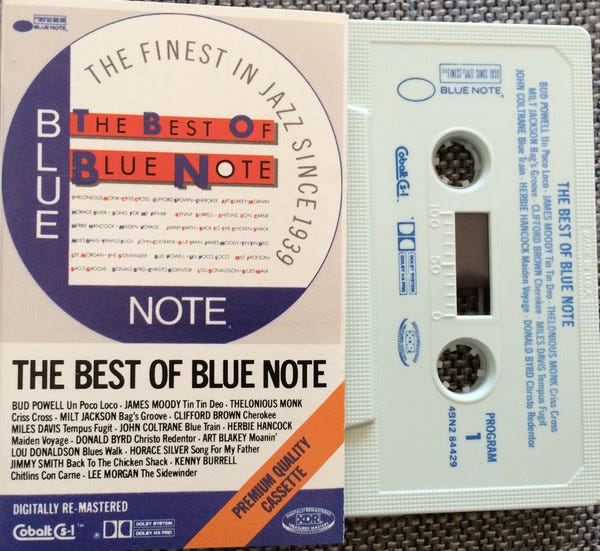

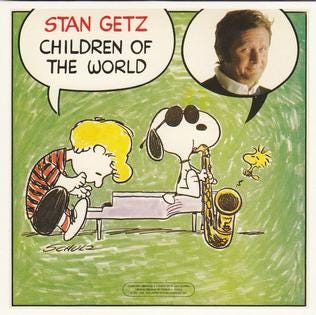

STAN GETZ - Children of the Word (Columbia, 1979) (LP/download/stream)

VARIOUS ARTISTS - The Best of Blue Note (Blue Note/Manhattan/Capitol, 1984) (2xLP/cassette)

Yes, I’m going to be showing my age multiple times in the process of writing this. Ask me if I give a meep-meep.

I’m going to be 57 this coming July 17. That’s a good lifetime of absorbing all kinds of music. I came into being just as the Billboard Album Charts had Sgt. Pepper, Headquarters, Surrealistic Pillow and the Doors’ first album in its top ten. Liver cancer had just promoted John Coltrane from living legend to sainthood that same early morning, by which time my mother was already in the maternity ward waiting for me to pop out (which wouldn’t happen until fifteen and a half hours after Trane left this dimension). By the time I was two, my grandmother already had me reading, my grandfather was showing me basic musical theory, and there was a little network called NET that would soon morph into PBS - where I’d see random jazz artists on both Sesame Street and Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood (especially the latter since Fred Rogers, himself an adept composer, had a crack jazz group led by pianist Johnny Costa and guitarist Joe Negri doing the musical scoring for his show), And how could we not forget now-classic animation’s infiltrating American households (especially the younger occupants thereof) via Warner Bros. shorts like The Three Little Bops and primarily the Peanuts TV specials, where Schroeder was, when he wasn’t paying tribute to his hero Beethoven, being the onscreen ivory-tickling doppelgänger for that series’ first composer, fellow July 17th baby Vince Guaraldi. (Hell, the soundtrack album to A Charlie Brown Christmas is practically the second-best-selling jazz album on the planet behind Kind Of Blue!) Seriously, show me someone that isn’t into jazz, play them “Linus And Lucy”, and when they react with “Oooh! The Charlie Brown theme! I love that song!”, do the following three things:

Politely correct them and tell them that the actual name of the song is “Linus And Lucy”, not the “Charlie Brown Theme”, which is an entirely different composition by the same composer.

Tell them “Congratulations, you like jazz after all,” then sit down and play them Kind of Blue and A Love Supreme.

Count the days until they call or text you with the news that they’ve bought their own copies of the aforementioned albums and have been obsessively listening to every other Jazz album that they can listen to on streaming.

And that’s where my own life experience comes in. I didn’t buy Kind Of Blue and A Love Supreme until I was a young adult in the early 90s with a CD player, and those early editions of the CD weren’t like the ones you can buy or stream now. My original copy of Kind Of Blue was Columbia’s first American CD edition, the 1986 Columbia Jazz Masterpieces edition that had been remixed to two-track digital tape and had mistakenly used a picture of electric-era Miles Davis, printed backwards, on the cover, rather than the classic closeup of a nattily attired Miles that’s on the original cover. All editions since then have been based on the original master plus someone at Sony Legacy realized that all three songs on Side A were playing a bit sharp ever since the album first came out, hence the speed correction that has been on every copy of Kind of Blue since 1997. My first copy of A Love Supreme was also a 1986 edition, basically the first CD edition of it ever, released on MCA Impulse! with a different font on the cover than the original LP; a 1995 edition in a digipack would later supersede that edition - and even then, that’s been superseded by later remastered editions in 2005 and 2015.

But those albums were not the first jazz albums I would hold in my hands and incorporate into my collection. Nope, that would first be attributable to an album with Charles M. Schulz’s iconic artwork on the cover - and it wasn’t a Vince Guaraldi album.

For some reason, the library in my junior high school had amongst its magazine offerings Down Beat magazine. Someone must have been very enlightened to have the school receiving copies of the magazine. The school’s library was a much quieter place for having lunch back then, so I’d go there every afternoon with my bag lunch and read there. And it was one of those times when I was reading Down Beat and noticed a magazine ad from Columbia Records and their sister labels with their latest jazz offerings - including one with a cover featuring Schroeder playing piano while Snoopy, in Joe Cool mode, played a tenor sax that had Snoopy’s avian BFF (and my all-time favorite cartoon character ever) Woodstock floating out of the sax’s bell.

I knew it was a jazz album - duh, it was in Down Beat magazine with other jazz albums from that time period. (I tried to Google for a scan of the print ad, but didn’t find one.) I never owned any jazz albums and didn’t know anyone that did - most of my peers were into their older brother’s classic rock albums - and if they did, they probably were more into jazz fusion back then, anyway - while I was listening to Cheap Trick, The Who, Kiss and everything punk and new wave had to offer that I could get my hands on at the time. I didn’t know the difference between bebop, swing, free jazz, or any other sub-genre that jazz had spawned. I just figured that the next time I was at the record store, I’d find the jazz section and see if I could get my hands on this album, even if only because it had a Peanuts cover.

I wasn’t exactly disappointed. No, Children of the World is not a groundbreaking jazz album in the vein of Kind of Blue, A Love Supreme, The Shape Of Jazz To Come, Mingus Ah Um, Bitches Brew, Time Out, or any other album you could care to name. But it is a good album. And Stan Getz is a legend in his own right on the horn, with a very smooth tone compared to John Coltrane or Pharaoh Sanders - but far from the lifeless tone that Kenny G would force practically at gunpoint on American ears by the mid-80s. After all, there’s video evidence (from a European TV show) of John Coltrane and Stan Getz having a blowing session together around 1960.

Children of the World saw Getz collaborating with Lalo Schifrin, he who is best known for writing film and TV scores (including the theme to Mission: Impossible) even though his early recorded output includes a few jazz albums for Verve Records. All of the compositions were Schifrin’s except for the opening track, a cover of “Don’t Cry For Me, Argentina” from the musical Evita - which must have made Schifrin a little uncomfortable, having left Argentina during Eva Peron’s reign and become a naturalized American citizen. A lot of the compositions Schifrin contributed to the album seem to tie in at least in some loose manner to the album’s general theme, inspired by the United Nations’ International Year Of The Child - at least, that’s what having song titles like “Hopscotch”, “You, Me, and the Spring”, “Summer Poem”, and the title track seem to suggest.

An AllMusic review of the album complains about what the writer feels are the excessive keyboards and the amount of poppish material. But that’s a bullshit complaint. Outside of the fact that one of the songs on the album, “On Rainy Afternoons”, had also been recorded in vocal form by Barbra Streisand the same year on her album Wet (Babs certainly liked her themed albums), plus the aforementioned Evita cover, the album isn’t exactly poppy and it certainly isn’t avant-garde either. Is it a pleasant listen? Yes? Does it still hold up to my ears after irregularly visiting it whenever I’m in one of my periodic jazz-listening moods? Absolutely. For a 12-year old CJ, it was a good first jazz album to have and enjoy.

Sadly, this album never came out on CD in the US. There was a French edition in the early 90’s and a Japanese edition in 2015, but the only American reissues have been in digital form. I’d suggest hitting up Qobuz and buying the FLAC files if you don’t want to get into a Discogs dogfight.

I wouldn’t get more seriously into jazz until the mid-80’s. I was in a cover band at the time where we had an 18-year-old whiz kid on the drums — that got subsequently replaced at the time by an older, jazz-fusion snob who looked at my Minutemen, Black Flag and Flipper tapes with absolute disdain. “If you listened to at least ten minutes of jazz fusion, you’d throw all of your punk tapes away,” he’d always say to me with a sneer. Never happened (and never mind that all three bands had a better insight into jazz than he did, in their own ways). I was familiar with some of the jazz fusion of the day, but it wasn’t the jazz I was fully interested in at the time, save for seeing Miles Davis play “Jean Pierre” on Saturday Night Live around the time his comeback album The Man With The Horn came out, and buying Jaco Partorius’ first solo album not long after he’d been murdered by two bouncers. I listened to enough guitar players between all of my punk albums and tapes and the Slayer and Metallica albums the band’s lead guitarist had turned me on to at the time. No offense to George Benson, Wes Montgomery, John McLaughlin, or Al DiMeola, who I’ve all grown to love as much as my punk and pre-punk favorites - but I wanted to listen to Greg Ginn or Kerry King and Jeff Hanneman when I wanted to hear a guitar player blow. When it came to jazz at the time, I wanted to listen to horns and pianos and upright basses - not guitar players! I wanted to listen to the kind of jazz I often blundered into when channel-surfing cable TV in my bedroom or picking up a jazz broadcast on the local public radio station.

Enter the fact that Capitol Records had recently revived the Blue Note label, the seminal jazz imprint founded by Alfred Lion in the late 30s and dropped strings of now-classic jazz albums in an almost 40-year period between the late 40s and mid-70s. Blue Train, Maiden Voyage, Somethin’ Else, Back at the Chicken Shack, Out to Lunch, Song for My Father, Miles Davis Volumes 1 and 2, Thelonious Monk: Genius of Modern Music, Newk’s Time, The Sidewinder, Speak No Evil, etc., etc. I’d gotten a four-cassette set of the One Night At Blue Note concert that Capitol had held to commemorate the relaunch of the label, along with the first album by Stanley Jordan (one of Blue Note’s new artists), thanks to a relative of another bandmate that could get titles from Capitol Records at wholesale price. I then found out that I could write to Blue Note and get a printed copy of their catalog. Perfect! That’s how I found out about my next serious jazz album.

I learned that there was a compilation of classic Blue Note hits that could be had either on double LP or cassette. I ordered the cassette - duplicated on audiophile quality Cobalt tape rather than the usual ferric oxide cheapness your older brother’s Lynyrd Skynyrd tapes were being duplicated on - from a local store, helpfully giving them the catalog number of the release. I only had to wait a week to get it. Walked down to the store the day it came in, paid for it, and was already divesting the shrinkwrap from Blue Note’s trademark white cassette case and popping the cassette into my Walkman before I had even left the block where the store (a local storefront) was located. I pushed play and within seconds, I knew I’d made a wise investment. “Un Poco Loco” by Bud Powell - an aggressive piano trio setting with the drummer going “more cowbell” decades before Christopher Walken made that a meme - became my first gateway into the world of Blue Note’s classic master recordings. (For the purpose of clarification, One Night At Blue Note Preserved, while four long-players deep with brand new live performances by assorted surviving Blue Note alumni as well as Mr. Jordan and the label’s other two new signings, Charles Lloyd (who is still with the label today) and Michel Petrucciani. In other words, while it represented Blue Note as it started to re-emerge in 1985 and reflected a great deal of its past history, it wasn’t the original recordings.)

The next track, “Tin Tin Deo” by James Moody, threw me off a little. There was a vocal. I wasn’t expecting a vocal. But, as I would soon learn, Alfred Lion was willing to try almost anything when he was in charge - even some early avant-garde jazz from Eric Dolphy, Ornette Coleman, and Cecil Taylor. But the rest of the tape - all 93 minutes - was exactly what I was looking for in jazz. Thelonious Monk’s original version of “Criss Cross” (he’d rerecord it twice in later years for Riverside and Columbia), John Coltrane playing “Blue Train”, Clifford Brown doing “Cherokee,” Art Blakey doing “Moanin’”, Horace Silver doing “Song For My Father,” Jimmy fucking Smith doing “Back at the Chicken Shack”… forget it. I was in for life. It would not be until I entered the CD era that I would start building up the jazz part of my library, but The Best Of Blue Note compilation was the real starting point. And then, when I got into vinyl again in 2007, I started buying some of the same titles on that format.

It’s not completely precise as I think it should be now - there’s no representation of Eric Dolphy, Ornette Coleman, or Cecil Taylor on there (at the very least, Dolphy’s “Hat and Beard” from Out to Lunch) should have been on that tape), but the tape stuck with me. I’ve long since added a vinyl copy - pressed in 1984 by EMI’s Pathe Marconi plant in France, like many of Blue Note’s reissues and new releases at the time - to my collection.

Sadly, as this particular compilation stands, it’s out of print. There is a Best Of Blue Note 2-CD set in Universal’s ICON series, but the track sequence is a pale shadow of the original compilation, with only about half of the original 1984 double LP’s selections duplicated, and the second half of the second disc is dominated by post-1984 material - or rather, post-1990 material, as Stanley Jordan doesn’t get any love from his former label even though Magic Touch, his major label debut, helped put Blue Note back on the map. Four of those last five tracks seem to represent Blue Note being morphed into an “adult pop” label rather than just The Finest In Jazz Since 1939. And no, Eric Dolphy still doesn’t get any love either, even though Universal has dutifully kept Out to Lunch in print for the past twenty years. No thanks. I’ll stick with either my double LP or the Spotify and Apple Music playlists I made for everyone to hear that duplicates the original 1984 compilation, track for track:

But yes, those two albums were the gateway. I’ve been a better music lover for it.