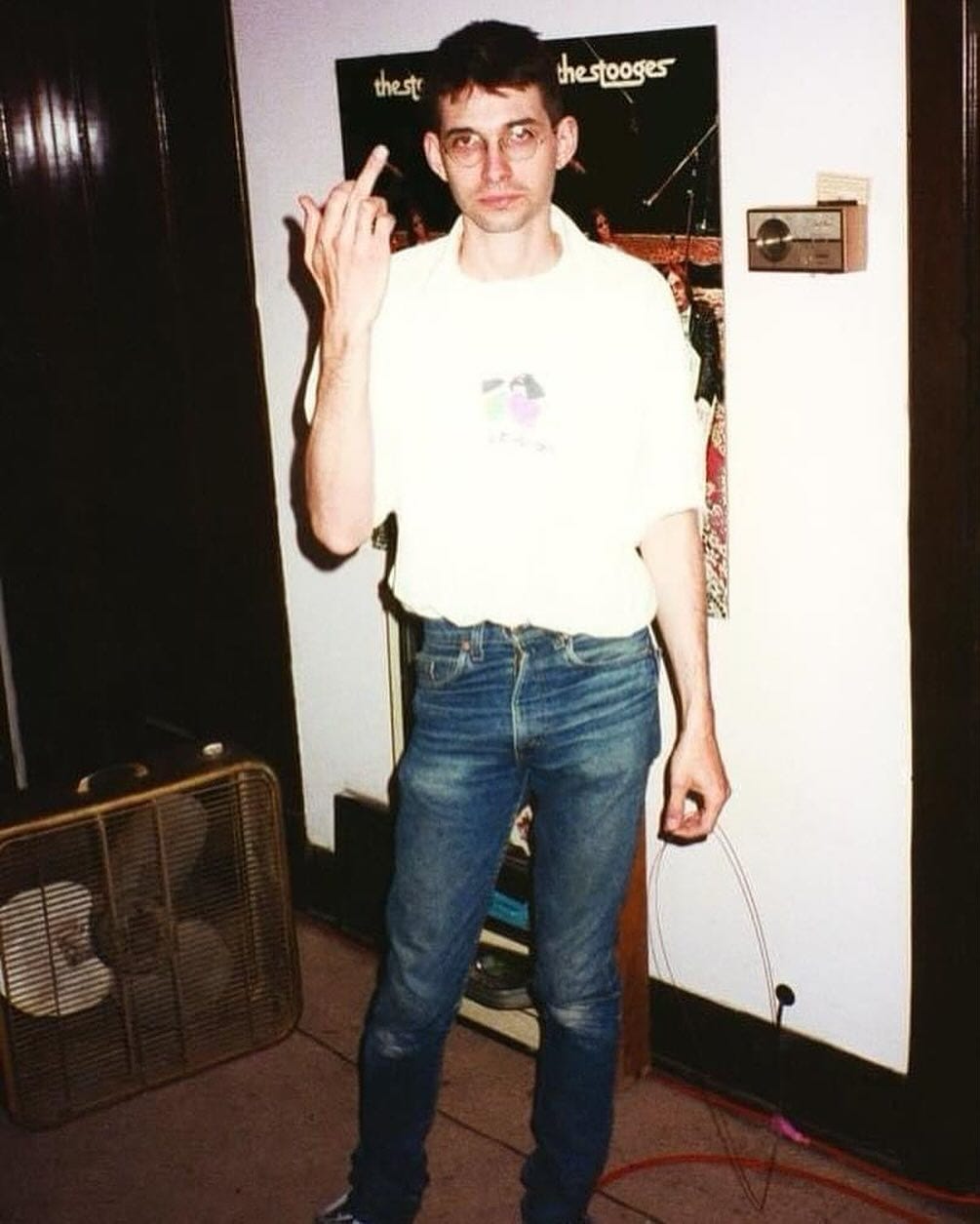

STEVE ALBINI, 1962-2024

The controversial musician, engineer, and sometime professional poker player has died at 61.

Steve Albini has transferred to the great recording studio in the sky.

The often controversial bandleader behind the post-punk pioneering trio Big Black and his successor bands Rapeman and Shellac died of a heart attack Tuesday night (May 8) at his Electrical Audio recording studio in Chicago at the age of 61.

According to various reports, Shellac - Albini’s longest-running band - was about to release their first all-new album since 2014’s Dude Incredible, entitled To All Trains, next week.

Albini first became known with Big Black in 1981 with the release of a six-song 12-inch EP entitled Lungs. Albini intended to recruit a full band before recording but had trouble finding people to play his songs to his satisfaction. (Or as Albini, who had his unique way with words his entire life, termed it, “I couldn’t find anybody who didn’t blow out of a pig’s asshole.”) Instead, having traded a case of beer for a week’s use of a friend’s four-track recorder, Albini recorded Lungs primarily by himself, playing guitar, bass, and some keyboard and programming a drum machine. The only outside collaborators were one friend adding a few “sax bleats” and a second adding a scream to one song.

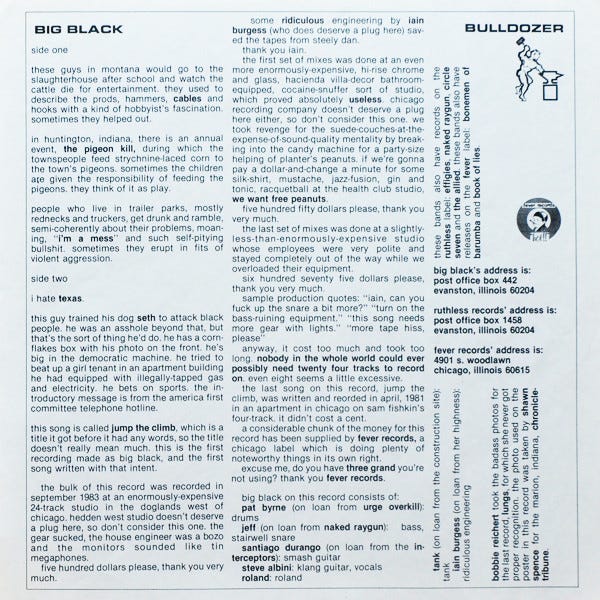

Albini then used Lungs as a recruitment tool to bring players into the band. Jeff Pezzatti, the lead vocalist of Naked Raygun, was Albini’s first recruit, coming in on bass. Still unable to find a drummer accurate enough for his liking, he concluded that the drum machine he used on Lungs would be more reliable, unlike most human drummers he’d encountered. Thus, the drum machine became Big Black’s other founding member, Roland - as in the TR-606 Drum Machine that would be the foundation for almost every Big Black recording that followed. Initial rehearsals at Pezatti’s house led Pezatti’s roommate and fellow Naked Raygun member Santiago Durango to join as co-guitarist and make Big Black a quartet (counting Roland). This lineup - with Pat Byrne of Urge Overkill serving as a session drummer to play alongside Roland (the only time live drums would ever be heard on a Big Black record) - went on to record Big Black’s first record as a full band, the 12” EP Bulldozer. That album’s insert would detail all of the sordid details of how Big Black dealt with the recording studios they used for the album.

And speaking of “sordid” and Big Black in the same sentence, Albini’s lyrics for the band were not strictly the typical punk rock lyrics. Albini’s lyrical topics frequently bordered on the anti-social and misanthropic - and at the same time, should not have been and should never be considered an endorsement of such depravity. Even on the opening track of “Steelworker”, Albini used the term “darkie” in the first verse simply because he found it ridiculous. “Dead Billy” depicted a PTSD-ravaged Vietnam vet. Bulldozer’s “Seth” is about a dog that had been trained to attack black people - and features a sample from an over-the-top racist phone line. “Columbian Necktie” is a harsh form of execution known to have been employed by despots.

One other common topic of Albini’s Big Black lyrics was small-town boredom. Having grown up in and escaped a small town in Montana to attend college in Chicago, Albini used songs like “Cables” (about youth going to a slaughterhouse to watch cows get slaughtered) and “Kerosene” (about combining casual sex with the town slut with equally casual arson - or maybe catching VD from said town slut if you interpret the line “Set me on fire” differently) to make fun of his small town upbringing - the total polar opposite of idiot bro-country artists glorifying such brain-numbing tedium in their shitty music. (Analyzing every Big Black lyric would be an article in itself.)

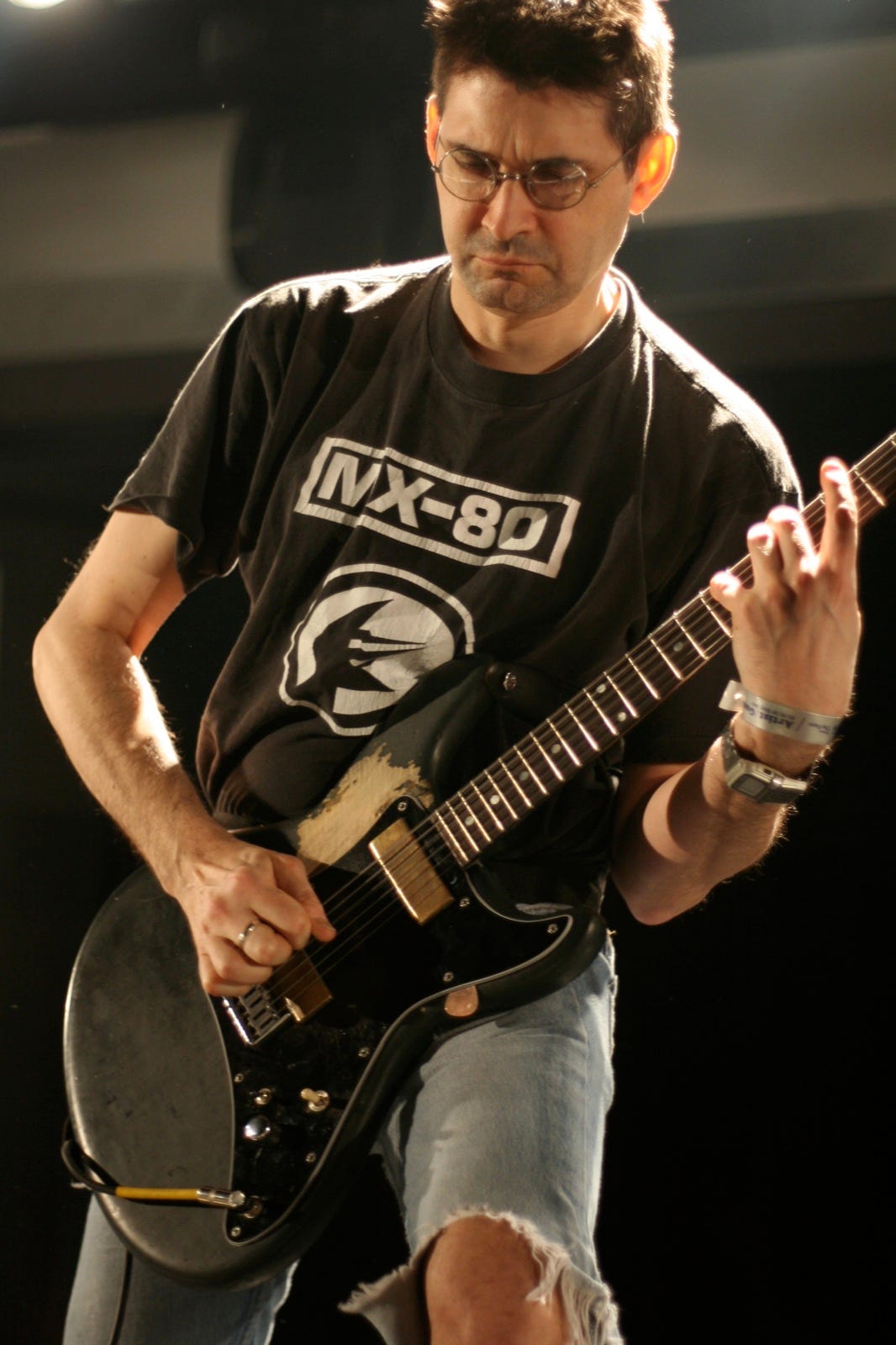

Steve’s guitar work was as abrasive as his lyrics. With Big Black, he started using metal guitar picks often modified with tin snips to create two side-by-side points. Later, with Shellac, he adopted Travis Bean aluminum guitars.

Albini was notoriously hands-on with Big Black’s business, doing everything from setting up recording sessions and rehearsals, booking tours, and doing business with labels differently than most artists. Having already released Lungs through one local label (Ruthless Records, no relation to the later hip-hop label), Albini conned a second local label, Fever, into financing the sessions for Bulldozer (both label’s logos and addresses would be printed on the insert). He scheduled rehearsals, booked studios for their recording sessions, and even booked the band’s shows and tours by himself. He notoriously declined to sign contracts with any label, presuming that a label would find a way to screw the band anyway.

"If you don't use contracts, you don't have any contracts to worry about. If you don't have a tour rider, you don't have a tour rider to argue about. If you don't have a booking agent, you don't have a booking agent to argue with."

Big Black would move on to the slightly larger Homestead Records to get their records distributed better, mainly because Albini was acquainted with label operator Gerald Cosloy (later of Matador Records). Albini negotiated a deal with Homestead where the band would retain their master rights, license their material for a specific time, not take advances or tour support, and finance the recording sessions themselves. This arrangement lasted until 1986 (more on that in a bit). After completing Big Black’s third EP, Racer-X, Pezatti left the band to concentrate on Naked Raygun (and his fianceé) full-time, while Durango elected to leave Naked Raygun and be a full-time member of Big Black. Pezatti’s replacement would be Dave Riley, then a member of the band Savage Beliefs and also, at one time, a recording engineer in Detroit with a couple of Parliament-Funakelic albums to his credit. This lineup would make Big Black’s first full-length album Atomizer, considered one of the band’s artistic peaks.

By 1986, Big Black’s problems with Homestead came to a head when Albini, already irritated with Homestead owners Dutch East India’s sketchy business practices, found out that a promotional single he had authorized had been duplicated beyond its 500-copy pressing and was being sold in stores. With that pretext, he immediately severed Big Black’s relationship with Homestead and moved the band’s back catalog and future releases to Touch And Go Records.

It was at Touch And Go where Big Black would release what is their second creative peak and second studio album, Songs About Fucking. Recorded partially at John Loder’s Southern Studios (best known as the studio where Crass recorded their entire discography, Fugazi recorded Margin Walker, and The Jesus And Mary Chain recorded their first two albums) and partially in Albini’s basement (the next phase in his musical career, as we shall see), Songs About Fucking was released after the band had called it quits (the band’s impending disillusion having been announced in advance before a final American and European tour). The main reasons for the split were due to Durango’s wish to concentrate on law school - and the increasing dipsomania of Riley, whose drunken behavior had led to some messy shows and, at one critical show, to the accidental “murder” of the original Roland. (An E-mu Drumulator would replace the late TR-606 on Songs About Fucking.)

After Big Black’s final show (which was captured on videotape and saw the band destroy their equipment), Albini went on to form the short-lived trio Rapeman with the former rhythm section of Scratch Acid, releasing the EP Budd and the LP Two Nuns And A Pack Mule before calling quits on that band by 1989. Albini would later liken naming the band Rapeman to getting a bad tattoo - and tellingly, although the Two Nuns And A Pack Mule CD (including Budd) can still easily be purchased new and is far from a bad listen, that band’s output would never make streaming or download services.

Post-Rapeman, Albini would enter a professional double life, partly becoming a recording engineer/producer for his day job and playing with a new band, Shellac, on the side. Albini became more active as the former after the end of Rapeman; He’d been responsible for a few things outside of his own work with Big Black and Rapeman before 1987, but rarely under his own name (crediting himself as “Li’l Weed” on Urge Overkill’s Strange, I… and as “some fuckin’ derd niffer” on Slint’s Tweez). But come 1988, the flood of recording credits started coming: Pixies’ Surfer Rosa; Urge Overkill’s Jesus Urge Superstar and The Supersonic Storybook; The Jesus Lizard’s Pure, Head, and Goat; Pussy Galore’s Dial M For Motherfucker; The Breeders’ Pod; Tad’s Salt Lick/God’s Balls; Pigface’s Gub; PJ Harvey’s Rid Of Me. Much of Albini’s producing/engineering output throughout this period of his life would consist of smaller artists. It was that pre-1992 resume that led Nirvana to tap Albini to produce their third and final studio album, In Utero.

It should be noted that Albini hated being credited as a producer and hated the idea of collecting points from records he worked on. Almost every album he produced and engineered would bear the credit “recorded by Steve Albini” on the sleeve. He reflected on his experience when recording with Big Black and Rapeman, which was one reason he preferred to be billed as an engineer rather than a producer, feeling that the artist should be in charge of the session and thus telling the engineer what should be done. He also had understandable (and typically harsh for Albini) criticism for digital recording methods, preferring to record all of his clients on analog tape (although, mindful of keeping clientele coming to his studio, he did permit a ProTools rig to be installed in his facility, although he would often decline to operate it himself).

By the time Albini was in discussions with Kurt, Krist, and Dave to record In Utero, Albini had already started his third and longest-running band, Shellac, with bassist Bob Weston and drummer Todd Trainer. After three quietly released EPs (all out of print) on Touch And Go (The Rude Gesture: A Pictorial History and Uranus) and Drag City (The Bird Is The Most Popular Finger), the band’s formal debut came with the 1994 album At Action Park, which gained notice in the press when Albini insisted on the album being manufactured on heavy vinyl at EMI Records’ pressing plant in London, which usually specialized in doing classical records, with the CD edition coming three months afterward - such was Albini’s contempt for the compact disc format. (A compilation CD of Big Black’s post-Racer-X studio output, released just as independent rock labels were starting to adopt the format, would be cattily titled The Rich Man’s Eight Track Tape; Subsequent vinyl releases by Shellac would be packaged with an unlabeled CD copy of the album, inserted with no sleeve). Shellac would go on to release studio albums intermittently for the last three decades of Albini’s life: Terraform in 1999; 1000 Hertz (packaged extravagantly in a box simulating a reel of Ampex tape) in 2000; Excellent Italian Greyhound in 2007; and Dude Incredible in 2014. All are worth a listen or several, as is the last Shellac release to be issued in Albini’s lifetime, The End Of Radio, which collects the band’s two BBC sessions for The John Peel Show.

Shellac’s intermittent performances (many of which would be interrupted so that Albini and Weston could host Q&A sessions with the audience) would be partly due to Albini’s increasingly busy schedule as a recording engineer—having built Electrical Audio in 1995 (moving his operations from the house he and his wife lived in). Post-In Utero (an album whose final product he would have mixed feelings about), he would proceed to expand his horizons, sometimes working with major-label artists like Fred Schnieder, Bush, Low, Veruca Salt, Cheap Trick, and Robert Plant and Jimmy Page with the same work ethic he would use with smaller bands. Sunn O))) recorded their two most recent albums, 2019’s Life Metal and Pyroclasts, during a month’s stay at Electrical Audio, and they have been widely praised as Sunn O)))’s best-sounding albums. (And given the attention to detail that Greg Anderson and Stephen O’Malley are notorious for, that is saying something.)

While his peers respected his work, some labels - especially the major ones - often had issues with Albini’s production style. Geffen Records tried to pressure Nirvana to either remix In Utero or re-record it entirely with a different producer; they refused unless Albini himself would remix it, and he declined to do so - but after R.E.M. collaborator Scott Litt remixed a couple of the singles-worthy tracks, and Bob Ludwig did his mastering magic on the final album (including Albini’s original mixes), and the matter was settled. The Stooges’ comeback album The Weirdness had been recorded by Albini at Electrical Audio and had gotten some justifiable criticism for its sound quality - until it was revealed that when Iggy Pop and Ron and Scott Asheton had gone to Abbey Road Studio to supervise the final master of the album, the Stooges had made the mistake of scheduling the mastering session for the day after playing a particularly loud gig. Fugazi had gone to Chicago to record their A Steady Diet of Nothing album at Albini’s original studio but then elected to shelve the finished product entirely and rerecord everything at their usual studio. Cheap Trick had rerecorded their entire In Color album with Albini at Electrical Audio. Still, the end result remains officially unreleased, said to be a sonically and performance-wise improvement over original producer Tom Werman’s efforts.

Albini was an avid poker player outside of music, even participating in three World Series of Poker tournaments, winning gold bracelets in 2018 and 2022. In the Dave Grohl-directed Foo Fighters documentary Sonic Highways, the series’ opening episode about Albini and Electrical Audio has one scene where Albini talks matter-of-factly about his poker side hustle and admits he often played to help cover expenses either at home or at the studio.

I am somewhat saddened by Steve’s sudden passing as both a fan of his music and his production work. I would have liked to have recorded at Electrical Audio with a band sometime with Steve in his omnipresent boiler suit behind the mixing desk, even though I advocate digital audio. (I’m sure he would have had harsh words for what I do with Toy Piano - or at least for my parodying his pro-analog slogan from The Rich Man’s Eight Track Tape on the back of Toy Piano I.) My friends in the Philly ghost punk band Northern Liberties had the pleasure of recording their most recent album, Self-Dissolving Abandoned Universe, with Steve at Electrical Audio. Even though he was high in demand as a producer because of his reputation with Nirvana, the Pixies, and other legends, Steve always took the time to work with smaller bands. For that alone, he should be lauded.

Rest in Power and Record in Paradise, Steve. Thanks for being a big part of my music library.

As more information on Steve Albini’s passing and tributes to him become available, I will endeavor to update this article appropriately. Also, here's a quick editor’s note: Normally, I somewhat reluctantly utilize Spotify embeds when talking about albums, but I could not locate any of Steve’s work with Big Black or Shellac on that platform. Apparently, Steve quietly withdrew his two best-known discographies from Spotify for reasons not dissimilar to Neil Young’s - meaning the shitty sound quality compared to Apple Music or Bandcamp, the latter of which I have utilized here.

EDITED TO ADD, 5.18.04: The tributes to Steve were too numerous to try to incorporate into this article. My apologies.

Also: As of yesterday, owing to a prior decision by Albini in the buildup to the release of the new album, the Shellac and Big Black discographies quietly returned to Spotify the day To All Trains was released.